Monday, April 02, 2007

Zman Cheiruseinu – the Time of Our Freedom – in the Valley of Death

This past Shabbos HaGadol I was privileged to hear Rav Leventhal deliver his drasha about “political and spiritual freedom.” He introduced his topic with an awesome Halachic query that was posed to Rav Ephraim Oshri, the last Rabbi of Kovno, Lithuania, during the Shoah, the Holocaust.

As we know, the morning service [for men] begins with a series of blessings, in which we thank Hashem and acknowledge that we are free Jewish men. The middle of these three blessings is “shelo asani eved,” wherein we thank Hashem for not having made us slaves.

In the Kovno Ghetto [in Lithuania] there was a chazan, a cantor, named Avraham Yosef. Every morning when he was about to recite this blessing, he cried out to Hashem: “How can I recite this blessing, as we find ourselves under arrest and in captivity…how can a slave make the blessing of a free man, with the yoke of slavery around his neck? How can a slave who is crushed and disgraced, without enough bread and water…how can such a slave bless his Creator and say, ‘You have not made me a slave’? Is it not mere ridicule, like a deranged person devoid of sanity? A major principle of Jewish prayer is that it should be with proper intention [kavanna], and how can I utter such a blessing when my heart is not with me?”

An awesome question, indeed. Without providing the answer that the Rav who was asked this question gave, I believe the story below, adapted and combined from a number of sources*, will shed some light on this matter.

(*Main Sources: Rav Binny Friedman, Isralight and Yeshiva of Greater Washington Weekly News)

As we know, the morning service [for men] begins with a series of blessings, in which we thank Hashem and acknowledge that we are free Jewish men. The middle of these three blessings is “shelo asani eved,” wherein we thank Hashem for not having made us slaves.

In the Kovno Ghetto [in Lithuania] there was a chazan, a cantor, named Avraham Yosef. Every morning when he was about to recite this blessing, he cried out to Hashem: “How can I recite this blessing, as we find ourselves under arrest and in captivity…how can a slave make the blessing of a free man, with the yoke of slavery around his neck? How can a slave who is crushed and disgraced, without enough bread and water…how can such a slave bless his Creator and say, ‘You have not made me a slave’? Is it not mere ridicule, like a deranged person devoid of sanity? A major principle of Jewish prayer is that it should be with proper intention [kavanna], and how can I utter such a blessing when my heart is not with me?”

An awesome question, indeed. Without providing the answer that the Rav who was asked this question gave, I believe the story below, adapted and combined from a number of sources*, will shed some light on this matter.

(*Main Sources: Rav Binny Friedman, Isralight and Yeshiva of Greater Washington Weekly News)

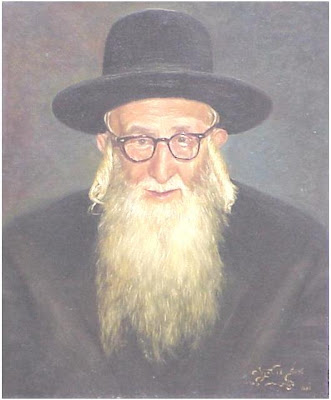

The Bluzhever Rebbe, ZTvK"L

*

It was the year 1942, in the foreign nationals section of the Bergen Belsen concentration camp. A group of Jews had approached Rav Yisrael Spira, the Bluzhover Rebbe, with an incredible request. Pesach was only two weeks away, and many of them, sensing this might be their last Pesach, were desperate to find a way to celebrate the festival. The thought of eating chametz (unleavened bread) was anathema to them, so they came up with an idea. They would appeal to the logical German mind of their oppressors and ask to receive their rations as flour and water instead of bread, and they would ask as well to build, on their own time at night, a crude oven with which to bake their rations into matza. After all, they reasoned, if the prisoners would start baking their own bread, this would be more efficient and economical, which would appeal to the mindset of their masters.

They asked the Rebbe if he would be willing to present their petition, signed by over eighty inmates, to the SS commandant of the camp, in the hopes that his merit and the merit of his illustrious ancestors would somehow protect them all and ensure a successful outcome. The Rebbe took some time to consider their request. Handing the Nazis a list of Jewish names was a very dangerous thing to do, especially in a concentration camp. Yet here was a group of Jews, enslaved, starving, almost beyond hope, and yet still willing to risk everything for the sake of a mitzva. How could he be the obstacle to the fulfillment of such a holy deed?

So the Bluzhever Rebbe asked for an audience with the camp Commandant, one Adolf Hoess, and approached him with his audacious request: “We wish to celebrate our religious holiday with matza. We are not asking for extra rations. All we ask is that you give us flour instead of bread, and that we be permitted to build a small brick oven for ourselves. All the work will be done outside of our regular working hours.”

To everyone’s amazement, not only did the commandant not have the Rebbe executed for such a request, but several days later, authorities in Berlin authorized it. Two weeks later, shortly before Pesach, the Jews of Bergen Belsen actually baked matza in preparation for the festival.

***

A few days before Pesach, a letter addressed to Switzerland was smuggled out, describing the deplorable conditions of the camp and requesting food packages. The letter was intercepted and given to Commandant Hoess, who charged into the barracks and berated the Rebbe: “I was kind enough to allow you to bake your filthy matzos and you repay me by sending out this letter! If you do not inform me within the next twenty-four hours who is responsible for this letter, I will have you shot.”

The Rebbe answered, “I know nothing of the letter and cannot be the cause of a fellow Jew’s death.”

As Commandant Hoess turned to leave he smashed the matza oven, but did not lay a hand on the Rebbe. Fortunately, the matzos had already been baked.

Since there were not enough matzos for everyone, it was decided that children under Bar Mitzva [13 years old] would not receive any matza. However, there was a widow in the camp, who had diligently cared for her two sons and three nephews throughout the war. While in the camp, she had even purchased a Tanach [Bible] with German translation for three pounds of bread in order to teach the children. The widow argued, “We must rebuild the Jewish people with our children. They are the ones who should receive the matza, for if we escape this Mitzrayim [Egypt], they are the future.” The Rebbe ruled that she was right, and the children were given matza.

Today, some of these children who learned from a Tanach bought with bread and ate matzos baked in tears, are leaders in the rebirth of Torah in Israel, America and England.

***

The Bluzhover Rebbe announced he would conduct a secret Seder in his barracks for those interested. Attending, never mind conducting, a Seder in Bergen Belsen was a crime punishable by death. Nonetheless, nearly three hundred Jews crowded into the Rebbe’s barracks that Pesach night. When they reached the point in the Seder that spoke of their bondage in Egypt, there was a palpable air of pain and anguish that spread through the barracks.

“Avadim Hayinu L’Pharoah b’Mitzrayim... Ata Bnei Chorin... - We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and now we are free men...’ The Rebbe could hear the sobs and feel the pain in every Jew’s heart, and knew he had to say something. How could a Jew recite these words in Bergen Belsen in 1942?

He looked around the barracks, in the dim moonlight, seeing the gaunt, hollow faces, and hopeless eyes, and he began: “Why is this Seder different from all other Seders? We have no four cups of wine to bless, no tables laden with good food and fine china, no children to ask the four questions, and no vegetables to dip in commemoration of the exodus from Egypt so long ago. Our matza, burned, small, and barely recognizable as the same matza we had before the war, reminds us more of where we are than of where we once were. Only maror, the bitter herbs, are in abundance this year. “But if even here, in the depths of our darkness and despair, we can nonetheless recall the exodus and celebrate Pesach, then we are truly free. Freedom, you see, isn’t about where you are, it is about who you are.”

***

The Bluzhever Rebbe taught them of surviving in slavery and of hope for redemption and freedom. He interpreted the ma nishtana to reflect the concentration camp experience. He told them that the Hebrew word avadim - “slaves” – had the same letters as the acronym for “David ben Yishai avdecha meshichecha – David the son of Yishai, Your servant, Your anointed to be Moshiach.”

Thus, “even in our state of slavery we find intimations of our eventual freedom through the coming of Moshiach. We who are witnessing the darkest night in history, the lowest moment of civilization, will also witness the great light of redemption... one day we will look back at this bitter exile night as the prelude of our redemption.”

It was the year 1942, in the foreign nationals section of the Bergen Belsen concentration camp. A group of Jews had approached Rav Yisrael Spira, the Bluzhover Rebbe, with an incredible request. Pesach was only two weeks away, and many of them, sensing this might be their last Pesach, were desperate to find a way to celebrate the festival. The thought of eating chametz (unleavened bread) was anathema to them, so they came up with an idea. They would appeal to the logical German mind of their oppressors and ask to receive their rations as flour and water instead of bread, and they would ask as well to build, on their own time at night, a crude oven with which to bake their rations into matza. After all, they reasoned, if the prisoners would start baking their own bread, this would be more efficient and economical, which would appeal to the mindset of their masters.

They asked the Rebbe if he would be willing to present their petition, signed by over eighty inmates, to the SS commandant of the camp, in the hopes that his merit and the merit of his illustrious ancestors would somehow protect them all and ensure a successful outcome. The Rebbe took some time to consider their request. Handing the Nazis a list of Jewish names was a very dangerous thing to do, especially in a concentration camp. Yet here was a group of Jews, enslaved, starving, almost beyond hope, and yet still willing to risk everything for the sake of a mitzva. How could he be the obstacle to the fulfillment of such a holy deed?

So the Bluzhever Rebbe asked for an audience with the camp Commandant, one Adolf Hoess, and approached him with his audacious request: “We wish to celebrate our religious holiday with matza. We are not asking for extra rations. All we ask is that you give us flour instead of bread, and that we be permitted to build a small brick oven for ourselves. All the work will be done outside of our regular working hours.”

To everyone’s amazement, not only did the commandant not have the Rebbe executed for such a request, but several days later, authorities in Berlin authorized it. Two weeks later, shortly before Pesach, the Jews of Bergen Belsen actually baked matza in preparation for the festival.

***

A few days before Pesach, a letter addressed to Switzerland was smuggled out, describing the deplorable conditions of the camp and requesting food packages. The letter was intercepted and given to Commandant Hoess, who charged into the barracks and berated the Rebbe: “I was kind enough to allow you to bake your filthy matzos and you repay me by sending out this letter! If you do not inform me within the next twenty-four hours who is responsible for this letter, I will have you shot.”

The Rebbe answered, “I know nothing of the letter and cannot be the cause of a fellow Jew’s death.”

As Commandant Hoess turned to leave he smashed the matza oven, but did not lay a hand on the Rebbe. Fortunately, the matzos had already been baked.

Since there were not enough matzos for everyone, it was decided that children under Bar Mitzva [13 years old] would not receive any matza. However, there was a widow in the camp, who had diligently cared for her two sons and three nephews throughout the war. While in the camp, she had even purchased a Tanach [Bible] with German translation for three pounds of bread in order to teach the children. The widow argued, “We must rebuild the Jewish people with our children. They are the ones who should receive the matza, for if we escape this Mitzrayim [Egypt], they are the future.” The Rebbe ruled that she was right, and the children were given matza.

Today, some of these children who learned from a Tanach bought with bread and ate matzos baked in tears, are leaders in the rebirth of Torah in Israel, America and England.

***

The Bluzhover Rebbe announced he would conduct a secret Seder in his barracks for those interested. Attending, never mind conducting, a Seder in Bergen Belsen was a crime punishable by death. Nonetheless, nearly three hundred Jews crowded into the Rebbe’s barracks that Pesach night. When they reached the point in the Seder that spoke of their bondage in Egypt, there was a palpable air of pain and anguish that spread through the barracks.

“Avadim Hayinu L’Pharoah b’Mitzrayim... Ata Bnei Chorin... - We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and now we are free men...’ The Rebbe could hear the sobs and feel the pain in every Jew’s heart, and knew he had to say something. How could a Jew recite these words in Bergen Belsen in 1942?

He looked around the barracks, in the dim moonlight, seeing the gaunt, hollow faces, and hopeless eyes, and he began: “Why is this Seder different from all other Seders? We have no four cups of wine to bless, no tables laden with good food and fine china, no children to ask the four questions, and no vegetables to dip in commemoration of the exodus from Egypt so long ago. Our matza, burned, small, and barely recognizable as the same matza we had before the war, reminds us more of where we are than of where we once were. Only maror, the bitter herbs, are in abundance this year. “But if even here, in the depths of our darkness and despair, we can nonetheless recall the exodus and celebrate Pesach, then we are truly free. Freedom, you see, isn’t about where you are, it is about who you are.”

***

The Bluzhever Rebbe taught them of surviving in slavery and of hope for redemption and freedom. He interpreted the ma nishtana to reflect the concentration camp experience. He told them that the Hebrew word avadim - “slaves” – had the same letters as the acronym for “David ben Yishai avdecha meshichecha – David the son of Yishai, Your servant, Your anointed to be Moshiach.”

Thus, “even in our state of slavery we find intimations of our eventual freedom through the coming of Moshiach. We who are witnessing the darkest night in history, the lowest moment of civilization, will also witness the great light of redemption... one day we will look back at this bitter exile night as the prelude of our redemption.”

*

A Chag Kasher v'Sameach - a Joyous and Kosher Pesach to one and all!